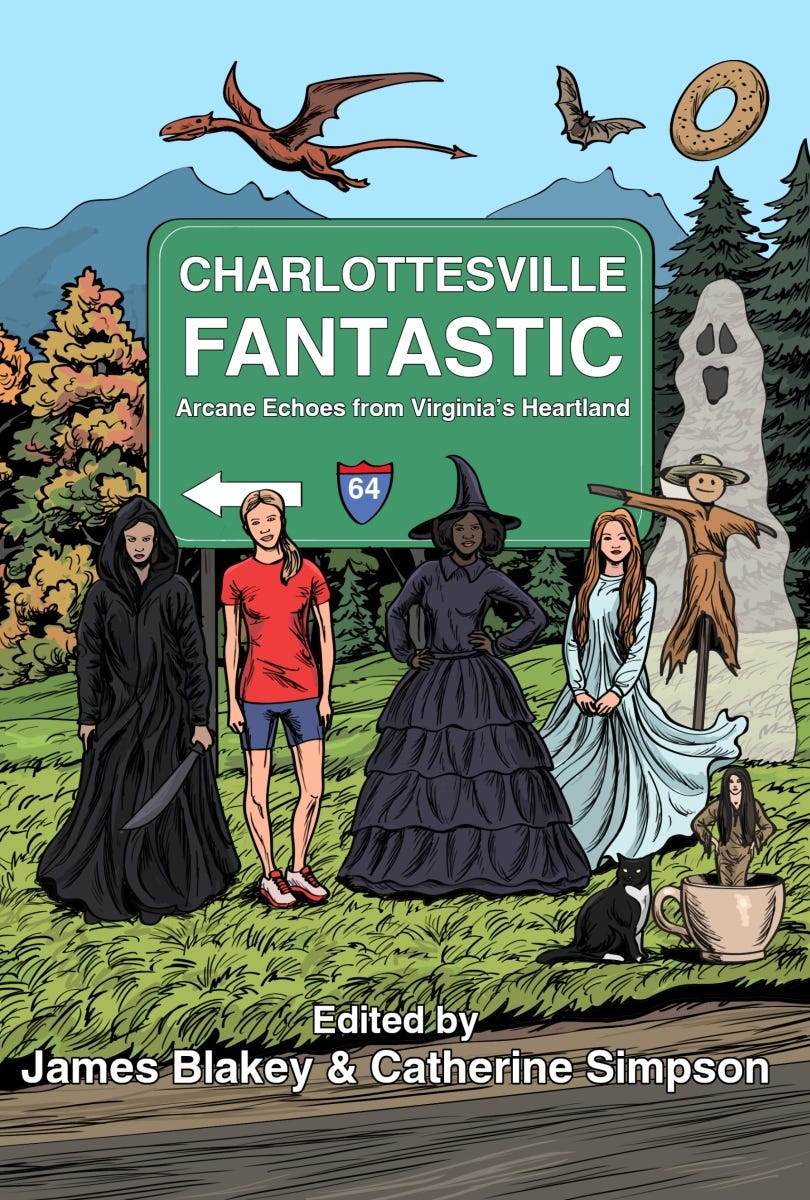

It finally happened: I have a short story getting legit published this fall. “Warriors of Kroas” is a prequel to the novel I’ve been working on the past two years, and will be included in Charlottesville Fantastic: Arcane Echoes from Virginia’s Heartland, an anthology of local sci-fi, fantasy, and speculative fiction. That means the speculative world I’ve created now has a canon, and that has changed and locked-in some plot points in the sequels.

Keep your eyes peeled for upcoming book events, including Parenthesis Books in Harrisonburg at 6pm on October 22, and the Crozet Book Festival on October 26!

I still have an on-again, off-again relationship with the idea of getting a novel published, with all kinds of conflicting feelings about taking up limited space in the highly competitive capitalist fiction market. I’m not trying to make money off my writing. I want it to serve the communities and movements I care about, and since the politically aligned presses I’ve approached are not taking on new projects right now, I’m considering making the novel available as a download in exchange for a suggested donation to a mutual aid or bail fund. What do you think? Would you read it?

In other news, my criminal case stemming from a lockdown action against the Mountain Valley Pipeline has been resolved. I pleaded the Virginia equivalent of “no contest” to two misdemeanors and received a fine and suspended sentence. Friends from the community saw to the fine, and I am grateful. I am still facing a massive civil lawsuit by the pipeline company, with no end in sight. I am also still facing charges stemming from a pro-Palestine protest and go to court in mid-September. I have reason to be optimistic that the most serious charge will be dropped. If that happens, I could go to trial for the misdemeanor. Guilty or not, this case could be all wrapped up instead of dragging out through next spring as I’d feared.

So what happens after that? For the past few months I have not allowed myself much leeway to imagine life beyond the coming year, steeling myself for the possibility of incarceration. I have been reckoning with the fact that the direct action I have poured my energy into for the past year has failed to stop the atrocities I’ve been fighting. Even the movement’s most disruptive tactics have failed to so much as slow down the genocide in Palestine, and the Mountain Valley Pipeline has gone into service while our capitalist system continues to accelerate us towards apocalypse. Nothing short of an indefinite general strike embracing a full spectrum of tactics will bring down the war machine, and we are years away from having the capacity to sustain resistance at that level.

The nomination of Kamala Harris has been a huge setback in that regard. It seems to have placated many restive elements on the left, renewing people’s commitment to our racist, capitalist, settler-colonial institutions. Energy that was going into resistance to imperialism is being diverted into an election, and likely won’t be coming back anytime soon if they win. People will not be building new structures as long as they believe the old ones might save them, even if it means throwing other communities under the bus to save our own dwindling privileges.

Consequently, I have slowed down. Organizers I respect have been calling on all of us to pump the brakes and shift our energies away from reactive mobilization and direct action campaigns towards slow, remedial, long-term organizing. If the past year has revealed how powerless we are to stop the capitalist death machine, it has also revealed where we need to get to work. We are powerless because we are dependent on the very system that is killing us. We need to build out new structures, new alternatives, rooted in the communities most directly targeted and marginalized by the system. In the face of mass deception and co-option, we need popular political education. In the face of housing and food insecurity, we need mutual aid and connection to land. In the face of right-wing and state violence, we need training in collective defense.

I have a little crew of folks in my community I am committed to building with, and we spent the past weekend doing some popular education with folks from around our region who are involved in food sovereignty work in various capacities. We were a multi-generational group of farmers, food service workers, organizers, educators, and students, all working through the Economics for Emancipation curriculum and discussing how the concepts explained there might apply to our everyday lives. It was a discussion that resisted capture by the electoralism that dominates our community, imagining different ways of making decisions together and distributing resources.

We were hampered by the conditions we organize under: Indigenous Monacan comrades couldn’t attend because a climate-driven tropical storm dropped a tree on their building, and poultry workers couldn’t attend because the bosses called them in for a last-minute shift. How do we surmount these obstacles that make it harder for the most directly affected to build power? How do we build resilient community ties rooted in mutual dependency and proximity when the forces of capitalism drive us into isolation? We would like to send representatives to the Southern Movement Assembly in Little Rock in September, but how do we do that when faced with things like work schedules, no vacation time, paying rent, and bail conditions prohibiting travel? The state and capital conspire to keep us hustling to survive, too tired and isolated to organize.

After spending two days wading through the machinations of capitalism and its impact on our community, we spent day three imagining new possibilities. Acknowledging that capitalism hasn’t always been the way things are or the way things have to be, we talked about three paradigms that movements have adopted as strategies of resistance: tame, smash, or escape. We talked about how reformist efforts to tame the system end up being just plain-old lame, but are sometimes necessary for short-term survival. The revolutionary strategy of smashing the system is high stakes, has a low chance of success, and often ends badly when it succeeds without a vision for what comes next. The anarchistic strategy of escape promises the possibility of utopia in the here-and-now, but is vulnerable to being crushed or co-opted by any system it leaves intact in the wake of its departure.

So why resist at all when the risks are so high, when the probability of success is so low? The answer is that people will resist when the status quo becomes too intolerable, when the cost of doing nothing is higher than what we risk by fighting for our freedom. To maximize our chances, we have to do all three things. We have to fight for incremental changes that erode and weaken the system (tame). We have to build alternative structures that reduce our dependency on the system (escape). And we have to take direct action that disrupts and dismantles the system (smash). “We need multiple strategies, practical steps rather than strict alternatives. We resist as we build, we plant as we uproot, fed by an underground railroad of fungal networks to redistribute abundance.”

We need multiple strategies, practical steps rather than strict alternatives. We resist as we build, we plant as we uproot, fed by an underground railroad of fungal networks to redistribute abundance.

It is going to take time - time that we do not have - to build and stitch together the structures we need to survive the coming collapse. We have years of building to do, and we’ve scarcely even begun to plan, much less dig the foundation, though I acknowledge we are not building from scratch. Here in the Shenandoah Valley, we’re talking about building third spaces, land trusts, public banks, and people’s assemblies. We’re talking about what to do with the abundance of food we’re always growing. And we’re talking about learning how to shoot guns. It’s going to be harder than it should have been had we started earlier, but as my dad always said to me when I wanted to procrastinate on an overwhelming job, “there’s nothing to it but to do it.” We can’t let ourselves be paralyzed by the magnitude of the task ahead. All we can do is start where we are and take it one step at a time.