Way back when I was in divinity school I had a favorite professor – the first Black professor to receive tenure from that esteemed institution – who taught from the tradition of Black Liberation Theology. His lectures so energized me that I took every class he offered that I could get into, and sat in on every class he taught even if I wasn’t registered. One of the points of common interest between us was our love of jazz, and he frequently drew on the jazz tradition to illustrate his points. I’ll never forget one of those points: if you want to have a say in the unfolding of the music, you have to get on the bandstand and play.

As a jazz musician I resonated. Anyone who has ever played jazz understands that it is a dialogical tradition. When you improvise a solo, you aren’t making anything up from scratch. You are joining in a conversation with every musician who has come before you, with your fellow musicians in that very moment, and you are contributing to the development of the music for the ones who follow. But the point of his analogy was this: you don’t contribute to the music from the sidelines. There is no such thing as an armchair musician. If you want to contribute, you have to get off your ass and blow.

A year or so after I finished divinity school I was on a training retreat with a bunch of organizers and activists, and two Black men in the group, both artists dedicated to dismantling white supremacy, got into a debate on the appropriateness of using the N-word in hip-hop (or anywhere, for that matter). I was standing nearby, half-listening, when for some reason they turned to me and asked, “Eric, what do you think?” I don’t think I missed a beat: “sorry, not my call.”

In that moment, I refrained from offering an opinion not because I was trying to be evasive or be a cop-out. I withheld my opinion because I didn’t feel I had a right to one. As a white person, I can’t imagine any scenario or context where it is appropriate for me to utter that word other than as an educational illustration of why it is off limits to me. In that particular instance, both parties to the debate acknowledged my point and resumed their conversation without me, and I sat back and listened and learned from their differing perspectives.

My point in offering these two anecdotes is this: you have to earn the right to participate in the intra-communal discernment of a historically oppressed community. I think that particularly pertains to conversations about liberation, and especially the tactics a people deploy to free themselves.

Around that same period of my life I thought of myself as a committed anarcho-pacifist, someone who believed that prefigurative politics required us to eschew the use of force in the pursuit of freedom and justice, along with a commitment to nonparticipation in capitalism and collectivism in daily life. I found myself in occasional debates about revolutionary methods with those very same Black comrades and mentors I mentioned in my two anecdotes above, and I think deep-down I felt the tension and inconsistency, the cognitive dissonance, in my behavior.

Even fellow pacifists poked holes in my framework. I read a fantastic history of the Black freedom struggle entitled There is a River, written by the theologian, activist, and political theorist, Vincent Harding, that showed nothing but reverence for the contributions of figures like Denmark Vessey and Nat Turner. Even this prominent exemplar of nonviolence had no criticism for those who used other methods to strike out for their own liberation. I discovered that, for Harding, “by any means necessary” meant that nonviolent direct action was but one legitimate means among many, and his eventual alienation from his chosen Mennonite tradition was in large part due to the racist, paternalistic push-back he constantly weathered from white pacifists who insisted on dictating terms of what is and is not legitimate resistance.

And so I slowly learned that my belief in the rightness and universality of my beliefs in nonviolence were a form of white supremacy, a form of armchair critique that set me apart from and above the messiness of struggle. If I wanted to be a part of the revolution, I had to get on the bandstand and blow, even if some of the notes sounded dissonant to my ears. At my core I did not want to be in the position of paternalistic white critic. It was wrong for me, as the privileged oppressor, to set the terms for what tactics and strategies the oppressed could or should use for their own liberation. Only the oppressed got to do that. Either I was an ally or I wasn’t. I could swallow my discomfort and offer my unconditional support, or I could get out of the way. I couldn’t have it both ways.

The irony of this shift is that it led me to a long excursion through leftist liberalism. That is because the vast majority of the people of color around me rightly believed that it was important to be effective. My friends and colleagues were not so interested in prefigurative politics that valorized precarity (a privileged perspective in itself) and elevated means so far above ends that little changed about their material conditions. So I got involved in what everyone around me was doing: non-partisan, issue-based community organizing that stressed policy change through grassroots power-building and pressure tactics targeting elected officials. I still stand by many of the organizing methods I learned in those spaces, but I also think history has proven much of my reformist campaign work around economic opportunity and policing to have been a dead-end at best, and reactionary at worst. The movement has moved on (especially since the return to prominence of the police abolitionist movement), and so have I.

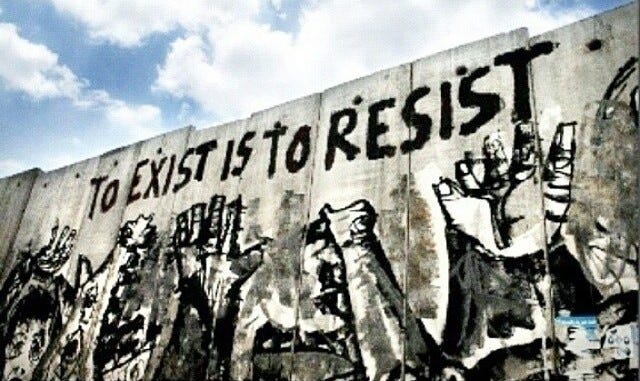

I am telling this long story because right now, all of us here in the West are being told we must take a position on the rightness or wrongness of Hamas’s actions on October 7, 2023. Condemning Hamas has become a litmus test, a requirement, for having the right to say anything at all about Gaza. So my response to the one who demands that of me is to flip the question: What have you done to support Palestinian resistance? What have you done to earn the right to an opinion on the methods Palestinians employ to achieve their liberation? Have you shared in the risks? Have you shared in the material conditions that Palestinians have lived under, day in and day out, for 75-years? I most certainly have not earned the right to condemn Hamas or any Palestinian who chooses the path of armed struggle. These are questions that challenge not just those of us (like me) who are descended from colonizers and enslavers. It is for all of us who do not share in the collective trauma of the ongoing Nakba.

In his partially complete, posthumously published work, Ethics, the anti-fascist German theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, warns of the dangers of the conscience, which sets the would-be follower of Jesus over and against the messy responsibility of living in solidarity with human life. As a theologian Bonhoeffer insisted that Jesus did not separate himself from the world, from the messiness of human life, but embraced it. Many see this as the ethical underpinning of Bonhoeffer’s participation in a plot to assassinate Hitler, an act of violent resistance that many pacifist Christians find disturbing, and which got him executed on Hitler’s personal order.

For me, resistance is a responsibility undertaken in accountability to those most affected by oppression. In the case of Palestine, that means writing a blank check to the resistance. My support is unconditional because Palestinians have the right and responsibility to choose for themselves the methods they will use to defend their communities and free themselves. My stake in this is my own liberation from the colonial project that claims me as its legacy, that takes away my humanity and makes me a settler, that makes me “white.” But only the subjects of colonization can lead the movement that topples it. If I want to get free, I must become their accomplice.

My unconditional support brings up a new kind of tension, however. One could argue that I am abdicating moral responsibility for my actions, that I am embracing ethical passivity by putting the work of discernment in the hands of others. With that blank check I am making myself into an unthinking foot soldier. There is a grain of truth in this. For me, resistance means, in part, that I show up asking what is demanded of me and not asserting my personality or taking charge or playing savior.

But I accept responsibility. Supporting the resistance means getting my hands dirty. I am still making a choice, and it is a choice rooted both in my own power and privilege and in my human agency. Insofar as my freedom to choose is rooted in my privilege, it is a symptom of a problematic structural reality that none of us can fully escape without abolishing the structure itself. My privilege gives me the option to withdraw, to set conditions, to pick sides in intra-communal debates and choose the side that I find more appealing or comfortable, to choose who I share my time and resources with. For better or worse, I do have agency, so when the chips are down, I choose to lean into the paths and positions that make me the most uncomfortable, that put more skin in the game, because often those are the paths most poised to dismantle the systems that imprison me in my privilege.

Being open to resistance “by any means necessary” shouldn’t mean I am in a constant state of escalation. Just as insisting that nonviolence is the only right way to do things in all times and places is a form of supremacy, so is any rigid adherence to absolutes and universals. There are moments when the people I’m throwing down with call me to greater risk, and there are moments when they put on the restraints. Part of earning my right to weigh-in means being trustworthy and not popping off like I have something to prove. Sometimes being in accountability means stepping back. Sometimes it is recognizing that I have a lane and need to stay in it, and let others handle their business their way.

Just as playing jazz is a kind of conversation, so is resistance. To riff off Vincent Harding’s book title, resistance is a river that flows through time and space, changing shape as it goes, learning from the past, adapting to the present, and carving new channels into the future. It is never the same thing everywhere and always. Embracing a diversity of tactics and upholding the right to resist by any means necessary really means diversity and every means. Perhaps it is no accident that the Palestinian resistance named their October 7th operation Al Aqsa Flood. Water is powerful and relentless. Water sculpts the land. Water always wins (credit to Doctor Who for that one). To carve new channels means reshaping reality with a tremendous outlay of power and energy to shift the momentum of an intolerable status quo, compelling your oppressor to react. I give the resistance my unconditional support even though this violent work of decolonization is messy and painful and makes me uncomfortable, because it is only by leaning into my discomfort and risking myself that I earn the right to be here, and here is the only place I know where my own liberation can unfold.