Colonialism has always looked like people burning alive in tents.

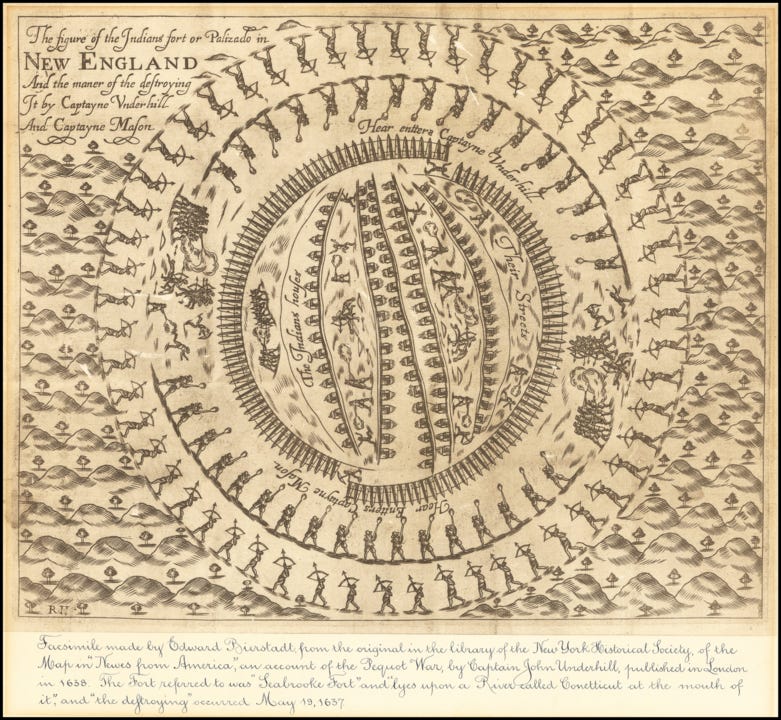

Not long after I saw the image of 19-year-old Palestinian Sha’ban al-Dalou burning to death in October after an Israeli airstrike hit the hospital tent where he lay hooked to an IV, I thought of the Narragansett people who my ancestors burned in the Great Swamp in so-called Rhode Island on December 19, 1675. I thought of the Pequots who perished at Mystic on May 26, 1637, another colonial atrocity to which at least three of my ancestors were party.

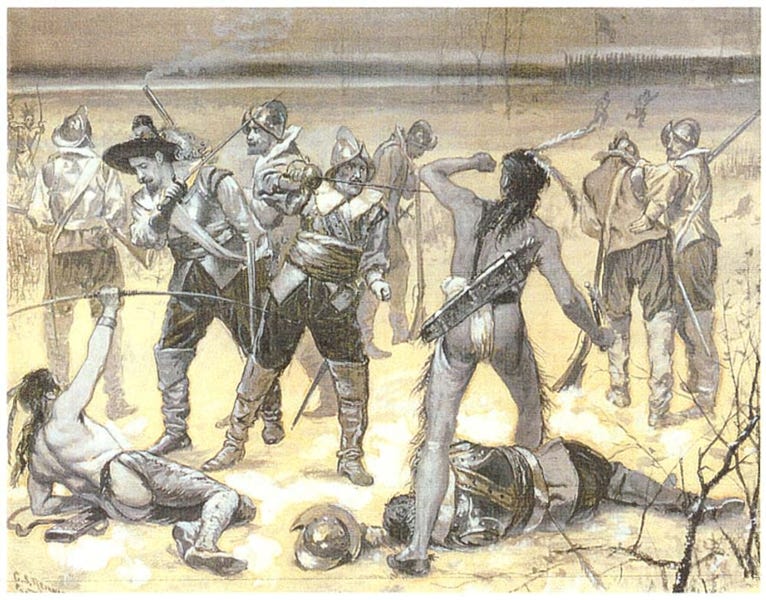

The Pequot War had threatened to become the first intertribal uprising against English encroachment, but the liberal Roger Williams (my step 9th-great grandfather) had showed his true colors, siding with his frienemies in Massachusetts Bay by brokering an alliance with the Narragansetts who were being tempted to join with their traditional Pequot enemies against the colonists. The Narragansetts participated in the attack on Mystic Fort. Even so, as they witnessed English methods of total warfare that refused to take captives or spare women and children, their warriors protested: “It is wrong, it is wrong, because it is too furious, and slays too many men!”

Captain John Underhill, who commanded the troops at Mystic, justified the slaughter he presided over by saying that “When a people is grown to such a height of blood, and sin against God and man, and all confederates in the action, there he hath no respect to persons, but harrows them, and saws them, and puts them to the sword, and the most terriblest death that may be. Sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with the parents…We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings.”1

The first public thanksgiving proclamations in the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut colonies rang forth to celebrate the genocidal slaughter of the Pequot War.

Of course, the English did not honor their obligations to the Narragansett alliance, and they would unleash the same fiery tactics on their erstwhile allies during King Philip’s War a generation later at the Great Swamp, once again killing multitudes.2 The war’s ending was the period at the conclusion of the “Thanksgiving” story: the capture and beheading of Massasoit’s son Metacomet, the Wampanoag sachem who led the first intertribal resistance against colonialism on Turtle Island. But the decentralized resistance did not die with him. The Wabanaki Confederacy to the north carried on undefeated, their notorious hit-and-run tactics largely halting English settlement to the north until the 1760’s.

The tent massacre on the grounds of Al Aqsa Hospital in 2024 is but the most recent in a centuries’ deep tradition of ultraviolence that links the Puritan holy warriors of my ancestry to the Zionist fighter pilots who terrorize Gaza today. It is a bloody tradition that cannot be whitewashed away with innocuous expressions of gratitude. That is why, as the US sits down to celebrate colonialism with a feast once again, I am observing November 28th as a day of reflection and mourning and reparations, as has become my practice the past few years. Just as I acknowledge the continuity of colonial genocide, I honor the freedom fighters who are linked in resistance across time and space, from Metacomet to Chief Greylock to Sinwar.

My commitment to repair has shifted as conditions have evolved one year over the next. In previous years our family has made reparations payments to tribal communities on lands my ancestors colonized, and I have dedicated much time and energy to supporting Landback initiatives with a nationwide scope. This year, however, I am focusing my energies on building a cooperative economy for survival and resistance with people I have direct relationships with in the place where I live.

In his text Reconsidering Reparations, Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò argues that reparations cannot just be about repairing relationships or addressing past harm. It must also be about building a better future for all. To me, this means we must be careful and intentional about the mechanisms we engage when doing reparative work. There are many attempts at repair that I fear rely too heavily on capitalist and/or state institutions, and therefore will not result in a true redistribution of power or wealth, and may in fact perpetuate harmful patterns of exploitation and violence, winning gains for one marginalized community at the expense of another. These are the empty promises of the politics of representation within the horizons of racial capitalism. An Indigenous organization that proclaims “Landback” should understand that this also must mean “Free Palestine,” because both are demands for an end to imperialism and settler colonialism if they mean anything at all. A Black-led institution that relies on electoral politics and capitalism to achieve self-determination will inevitably become agents of imperialism and white supremacy.

Being the bearer of marginalized identities does not make one innocent of the temptations of racial capitalism. We are all subject to the same propaganda, and all of us live on the same colonized landscape, even as we experience its violences differently and disparately. The ongoing genocides unfolding across the globe in places like Palestine and Congo and Sudan, and the bi-partisan consensus that supports them, underscores the need for moral and political clarity here in the imperial core. The political establishment relies on our consent and our complicity to carry out its death-dealing work, and is happy to use BIPOC faces to manufacture that consent, and BIPOC and queer bodies as bargaining chips.

So while I bear a unique responsibility as an heir of my ancestors’ deeds and the so-called privileges they created (white privilege is a poison rooted in a pathological identity), solidarity with colonized peoples everywhere places a demand on all of us and calls us to a higher and broader loyalty. Reparations cannot mean a mere redistribution of plundered goods while the plunder continues. It cannot mean simply handing over the master’s tools so that everything can continue the same way under new management. Our collective work is to burn down the master’s house. A livable future for all depends on it.

Reparative work that relies on respectability, that relies on the good graces of colonial entities, can only result in temporary concessions, gains that will be rolled-back and paid for with permanent losses in the forms of mountains, rivers, and lives. As US institutions stand on the brink of a terminal descent into fascism, the incoming administration has every intention of rolling back the few hard-won gains made since 2021. That is why this is a perfect time to reject hope in liberal institutions and learn to trust each other. It also means we must commit to being trustworthy.

I admit that after many years of false starts and dead ends, I might be a little paranoid. Racial capitalism has perfected the art of co-opting movements, weaponizing our well-intentioned efforts to get free and turning them against us. Not knowing what the future holds, what the next trap might be, I want to move slowly but deliberately, staying accountable to my community and the movements I care about. I don’t want my actions in the name of liberation to become someone else’s chains. We have a responsibility to each other and to the coming generations.

Some of us will eat together and give thanks this week, but we are doing it the day after the skipped colonial observance, coupled with a ritual of lament and remembrance. As we do so, I recognize how the burden of guilt I’ve inherited from my ancestors tells me that I have no right to my own survival, that I can never truly belong with the land, and that my politics should be purely nihilistic, about destruction and not building, leaving the work of building to those more deserving. But my people won’t let me stay in that mental and spiritual void. As a collective we are committed to both building and resisting, and we understand that these have to go together, that neither is sustainable on its own.

I hope that the multiple crises facing the world right now leads anyone reading this to reconsider their observance of colonial celebrations like Thanksgiving in light of our interdependence as human beings across the globe. I hope you, too, will come to see where you stand in the sweep of history, and see that you have a responsibility to be a good ancestor to future generations. I hope you will find your people and begin moving in solidarity with the colonized and dispossessed, caring for the land and your neighbors wherever you are, imaging beautiful futures beyond the death-dealing systems that control our lives and ravage our world.

James Warren, God, War, and Providence, 91.

For further reading on King Philip’s War, I recommend Lisa Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War.